Rare and Unlocated post-incunables

£21,000 | €25,000 | $27,000

Introduction

This visually attractive Sammelband contains unlocated and rare post-incunables, and includes two woodcut illustrations. The seven items are linked by their imprint location: publication 1 was likely printed in Paris, and publications 2–7 certainly were. Beyond this, however, the combination is somewhat eclectic. There are four instructions for priests, but these are sandwiched between a biographical compendium of ancient authors, a satirical dialogue attacking Pope Julius II, and a royal act relating to university privileges.

The collection survives in a contemporary binding, indicating that these seven publications were put together at an early stage. This in turn provides an interesting insight into the history of reading and compilation practices. The collection also sheds light on the practicalities and logistics of sixteenth-century pamphlet production, notably the faulty metalcut initial in publication 1, the stop-press change in publication 2, and the mistake in publication 4.

What follows is a description, a discussion of each of the seven items individually, and finally a consideration of the book as a whole—especially signs of use therein.

Left to right: publications 6, 7, 3 and 4.

Contents

A Sammelband containing the following publications:

- [Burley, Walter, pseudo-]: Vita omnium philosophorum et poetarum cum auctoritatibus et sententiis aureis eorundem annexis. [Paris?, de Marnef (device owner), c.1517 based on the device].

- [Erasmus, Desiderius]: Dialogus viri cuiuspiam eruditissimi festivus sane ac elegans, quo[modo] Iulius. II. ... post mortem coeli fores pulsando, ab ianitore illo D. Petro i[n]tromitti nequiuerit ... [Paris, Jean (/Gilles?) de Gourmont, c.1518].

- [Hustuberro, Bernardus de]: Itinerarium Clericorum. Paris, Jean du Pré (II), Pierre Gaudoul [c.1519 based on the device].

- [Instructions for Priests]: Instructio seu Alphabetum sacerdotum [...]. Paris, Jean Petit [1507 or later based on the device].

- [Instructions for Priests]: Cura clericalis Lege Relege. [Paris: Pierre Gaudoul (device owner), c.1515 based on the device].

- [Amelius, Joannes]: Instructio virorum ecclesiasticorum. Paris, Regnault Chaudière & Jean du Pré (II) [c.1520 based on the dedication].

- [Royal Acts]: Les reformatio[n]s des previleges des universitez. Avec le cry des monnoyes nouvellement publie a Paris. Paris, Guillaume Nyverd, 1506.

Physical Description

Seven publications in one volume, octavo, 14 x 10 cms in binding.

- Publication 1: fols. [96], collation: a–m8 . Printer’s device to title-page (Renouard, Marques, 721). Decorative printed initials up to six lines in height. 2.

- Publication 2: fols. [36], collation: A–I4 . Final folio blank. 3.

- Publication 3: fols. [24], collation a–c8 . Printer’s device to title-page (Renouard, Marques, 338). Decorative printed initials up to ten lines in height. Final page blank. 4.

- Publication 4: fols. [12], collation: a12. Printer’s device to title-page (Renouard, Marques, 883; Haebler 1914 IV). Decorative printed up to eight lines in height. 5.

- Publication 5: fols. [16], collation: A–B8 . Printer’s device to title-page (Renouard, Marques, 338). One decorative printed initial four lines in height. Final folio blank. 6.

- Publication 6: fols. XXIIII (i.e. 24), collation: A–C8 . Woodcut illustration to title-page depicting a monk writing in a scriptorium (9.5 x 7.5 cms). Decorative printed initials up to eight lines in height. 7.

- Publication 7: fols. [12], collation: A8 –B4 . Printer’s device to sig. B4v (Renouard, Marques, 839). One woodcut illustration: knights fighting on horseback with castle or city in background and a knight assisting an injured combatant in foreground (6 x 7 cms, sig. B4r).

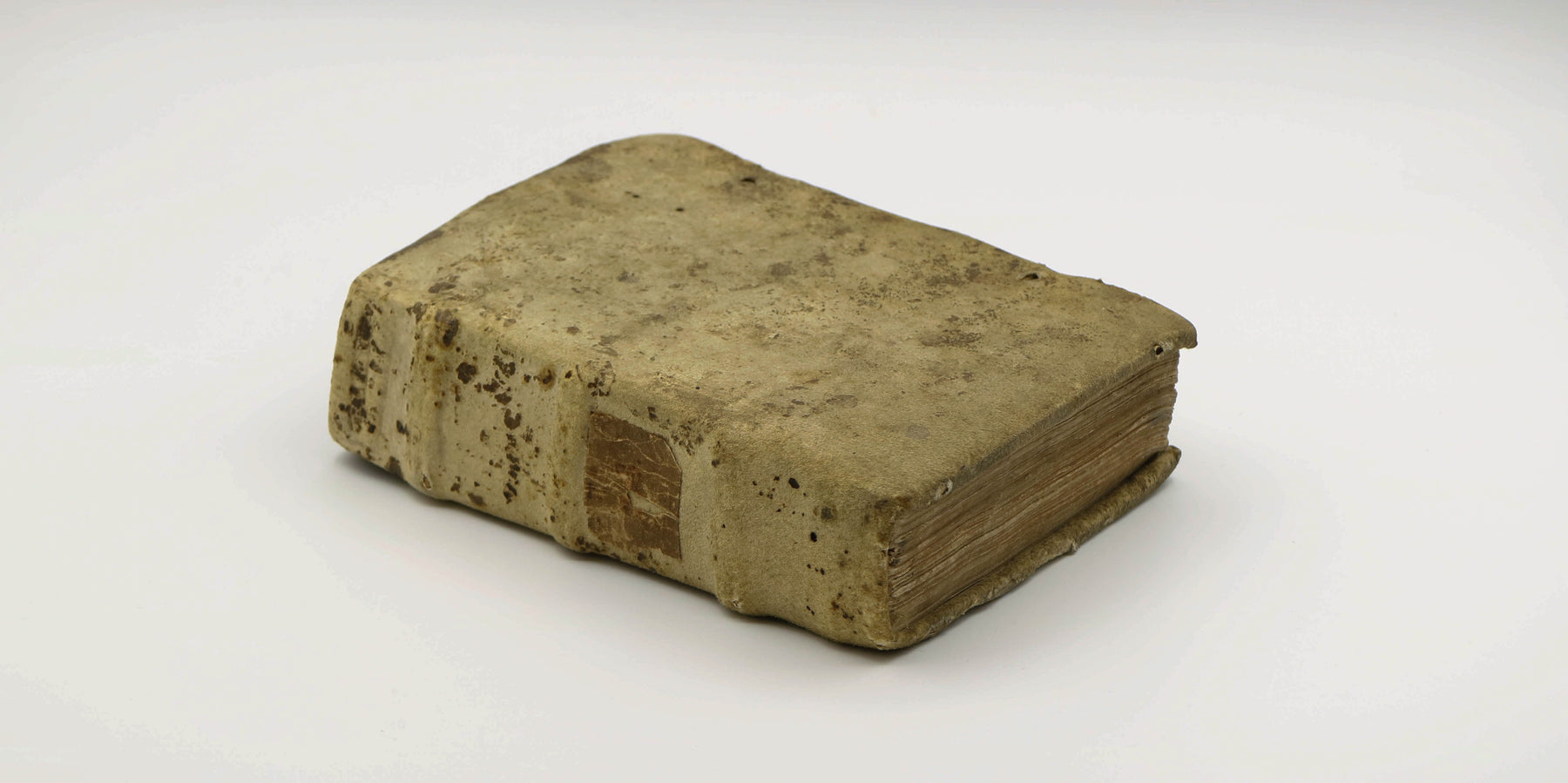

Binding

Materials: Contemporary green-stained reversed alum-tawed hair-sheep or goat over boards made of laminated sheets. This covering material was commonly used in French sixteenth-century bindings for ordinary (as opposed to luxury) books. Compare Médiathèque d’Orléans MS 73 (70), reproduced on the cover of Alexander and Lanoë 2004 and described in their catalogue entry as ‘peau mégissée’ (alum-tawed).

Sewing: Sewn on three supports.

Labelling: Remnants of a label to third spine compartment.

Ties: Two fore-edge holes for ties on front and rear covers; remnants of alum-tawed ties visible on inside of both boards.

Endpapers: No pastedowns. Three free endpapers at front and two at rear. One loose leaf with early notes of an owner who signs elsewhere in the volume, possibly originally a front endpaper but with no wormholes (the others have them). It was perhaps removed early on (prior to worming) and loosely enclosed somewhere with no worming (e.g. at end).

Guards: Two medieval manuscript fragments on parchment reused to form guards around the free endpapers. Both manuscripts have been trimmed into somewhat trapezoid shapes, and are written in late fifteenth- / early sixteenth-century cursive scripts (possibly documents?). The recto of the front guard has 10 surviving lines of text (clipped at both ends of the lines), with the text running parallel to the spine of the book. The verso of the front guard is largely blank but has remnants of 6(?) lines of text running perpendicular to the spine. The verso of the rear guard has 9 surviving lines of text running parallel to the spine (clipped at both ends of the lines). The recto of the rear guard is blank.

Condition of binding: rubbing and slight wear, very small tear to covering material at tail of spine, a few single wormholes to front cover and front endpapers (wormtrails at inside front cover), one small further hole to second front endpaper.

We are grateful to Nicholas Pickwoad for discussing this binding with us.

Condition

Textblock: light browning and soiling or staining to paper; single wormhole to the first 16 fols. of publication 1 affecting at most 1 or 2 letters per page; flaw affecting two words on sig. a8v in publication 5.

Binding: rubbing and slight wear, very small tear to covering material at tail of spine, a few single wormholes to front cover and front endpapers (wormtrails at inside front cover), one small further hole to second front endpaper.

Provenance

- Sixteenth-century hand-written correction to publication 4, ipse > spe (see discussion below).

- Multiple ownership inscriptions connected to a Jacques / Jacobus Prenost [or possibly Prevost], including ‘Ex Libris Magistri Jacobi Prenost’ (recto of first free endpaper at rear) and ‘Cest a Jaques prenost’ (faded, verso of second free endpaper at rear). Further ownership inscriptions possibly indicate that Prenost was a canon, e.g. ‘Cest a jaques prenost chan[oine(?)] de beaunoys [=beaunois?] [???] [???] pa[???] de Sion(?)’ (loose leaf enclosed at front; possibly a former endpaper). Prenost appears to be connected to at least some (and perhaps all) of the extensive pen trials in the endpapers, which have been used as a space to practice producing letter forms, ornamental flourishes, and passages of text (e.g. from Psalm 117). Prenost may also be responsible for the crossed-out signature on the final blank of publication 2, which appears to say ‘J Renost’ or similar (sig. I4v).

- ‘Hanc edit[ionem] Ebart [or Ebert(?)] i[am] habet’, ‘Hunc librum Ebart [or Ebert(?)] i[am] habet’ (title-page of publications 2–6).

- ‘Hand A’ (c.1700?) annotates several publications in the Sammelband, typically with underlining and nota bene marks (see discussion below).

- Annotations to title-page of publication 1 in a variety of hands, including what appears to be a sequence of names, places, and dates: ‘Parisiis jj Escks(?) Anno 1630’ ‘H Berger, Rili[??]e(?) 1828’ ‘Chr. Getersen Hamburgi 1850’. Annotations here also include ‘Mus. Saligr(?)’, ‘Lib[er] Rar[us]’, and ‘F CBDK(?)’.

- Pencil annotations to inner front and rear boards, ‘F(?) 120-’ and ‘LO-’ respectively.

- Nouvelle Etude, Paris, 10 November 2022, lot 56.

1) Vita omnium philosophorum et poetarum […]

A rare edition of this text historically attributed to the influential English philosopher Walter Burley (c.1275–c.1345), which comprises biographical accounts of significant ancient Greeks and Romans, especially philosophers. It is now attributed to pseudo-Burley (cf. Copeland 2016, pp. 248–50).

De vita et moribus philosophorum (as it is now more commonly known) was first printed in Cologne by Ulrich Zel c.1470. This popular text was also translated into vernacular languages including Spanish, Italian, and German (Copeland 2016, p. 249).

The printer’s device in the present edition was used by the brothers De Marnef and can be found in a publication from 1517 (Renouard, Marques, 721). The three brothers—Geoffroy (active 1485–1518), Enguilbert I (active 1491–1533), and Jean I (active 1504–1515)—were printers, booksellers, and publishers operating in Paris but also Angers, Bourges, and Poitiers (Walsby 2020, pp. 636–39). Several other Latin editions of De vita et moribus philosophorum by the brothers de Marnef are known, including two quartos ([Paris], Jean de Marnef, 1510, USTC 180440, FB 59514; [Paris], Enguilbert and Geoffroy de Marnef, for Jean Petit, c.1510], ISTC ib01327300, USTC 768214).

We have also identified a rare octavo edition of the text in the Universitäts- und Stadtbibliothek Köln ([Paris], de Marnef, [c.1510]). Despite having the same format, foliation, collation, and title wording as the present publication, it is not identical. Most obviously, it has a pietà illustration to the title-page where ours has a printer’s device, and fols. [1v], [95v], [96r] and [96v] are blank where ours are not.

Our publication is also very similar to an octavo edition printed c.1515 (Adams B3321; we have seen a selection of photos of the Newnham College Cambridge copy). While our edition has same format, collation, body text type, and at least some of the same initials as Adams B3321, the two publications have different bibliographical fingerprints. Moreover, the title page bears the device of Jean Petit rather than de Marnef. For comparison, the aforementioned quarto edition of Burley’s Vita printed by Enguilbert and Geoffroy de Marnef for Jean Petit c.1510 survives in both a version with Petit’s device and a version with a de Marnef device (as noted in ISTC ib01327300).

Further research might shed interesting light on the relationship between Petit, the de Marnefs, and Parisian editions of Burley’s Vita in the early sixteenth century. From an early printing perspective, the present publication is also notable for containing a faulty metalcut for the letter S; the letter is represented in mirror image every time it appears (i.e. at the beginning of chapters 38, 83, 93).

2) Dialogus viri cuiuspiam eruditissimi [...]

A rare edition (with an even rarer stop press change) of a satirical text more commonly known by the title Iulius exclusus e coelis. The text, which is generally attributed to the Dutch theologian Erasmus (d. 1536), examines papal power and takes the form of a dialogue between Pope Julius II (d. 1513) and Saint Peter in heaven. The first edition of the text was produced by Peter Schöffer Jr. in Mainz in 1517—four years after the death of the Pope. Three further editions appeared in 1517 (Antwerp, Strasbourg x 2).

Our edition is one of two closely related editions of the text printed in Paris c.1518, both of which are associated with the Gourmont family of printers. However, there is a lack of consensus in the standard bibliographies about who specifically was behind these editions. BP16, FB, Moreau, and USTC infer Jean de Gourmont as the printer for both editions, while Erasmus Online infers Gilles/Jean de Gourmont.

Ferguson posited that our edition was a derivative of the other Gourmont edition, ‘with some corrections in spelling and one line omitted’ (Ferguson’s relevant catalogue card is reproduced on Erasmus Online 1089). If this is true, then it would seem that the compositor(s) inadvertently introduced an error when producing the revised edition. The title page of the copy in Rotterdam Public Library (reproduced on Erasmus Online 1089) incorrectly refers to Julius XI instead of Julius II. The present copy has the correct Papal number—presumably a stop-press change.

3) Itinerarium Clericorum

First edition of this instructional tract for priests by Bernardus de Hustuberro, the first of four consecutive instructional tracts for priests in this volume.

It opens with a preface addressed to parish priests and closes with a table of contents. Topics covered include the age requirements for priesthood.

There are four known editions of the text, variously produced in Paris between 1519 and 1525. This edition—the earliest of the four—was produced by the printer Jean du Pré (II) in partnership with the bookseller Pierre Gaudoul.

4) Instructio seu Alphabetum sacerdotum [...]

An unlocated edition of this instructional tract for priests, evidently popular in Paris in the early sixteenth century. The text includes directions for performing mass. FB lists 26 editions with the title Instructio seu Alphabetum sacerdotum or a slight variation thereof, over half of which were printed in Paris.

The earliest known edition was printed in Paris in c.1494–1495 by Georg Mittelhus (ISTC ia00532700). Like ours, many subsequent editions of the text were undated. Interestingly, this edition of the text contains a mistake in a section providing a prayer that the priest is supposed to say ‘in mente’ (i.e. in the mind) while performing mass, which a sixteenth-century hand has corrected in the margin. The correction (ipse > spe) is much faded.

The present edition was produced by Jean Petit (active 1492–1530), a prolific Parisian printer and bookseller who held the title of libraire-juré of the University of Paris (cf. also publication 1 above). Four editions of Alphabetum sacerdotum produced by or for Jean Petit are recorded in the standard bibliographies, but none correspond to our edition.

According to Konrad Haebler (1914), Jean Petit first used the device found in our edition in December 1507. This postdates two of Petit’s other editions of the text (ISTC ia00533150 [before 1497]; ia00533300, 1499).

5) Cura clericalis

An unlocated edition of another instructional tract for priests. To judge from the surviving corpus, Cura Clericalis was especially popular in France—though it was also printed in Germany and England. The text ‘defined four roles for the priest’, as Eamon Duffy helpfully summarizes:

He was to be a celebrant of Masses, and so needed to understand the basic texts and be able to pronounce the Latin grammatically and clearly. He must be a minister of the other sacraments […] He was to be a confessor, and so must be able above all to distinguish venial from deadly sin […] Finally he was to be […] the teacher of his people.

(Duffy 2005, p. 57)

Notably, Cura Clericalis also includes a short computus summary called ‘abbreviatio compoti’ (in this edition, see sig. b3v onwards). Computus is the calculation of time, especially the date of Easter.

The device on the title-page of the present edition belongs to Pierre Gaudoul, a Parisian bookseller also associated with publication 3 above. FB lists 29 editions of Cura clericalis, none of which are connected with Gaudoul. The earliest of these was printed in Caen [1511] (FB 63749), and the first Paris edition was produced by Jean Petit in 1515.

The present edition may be roughly contemporary with the first Paris edition, as our device is listed in Renouard, Marques with reference to a book printed in 1515 (no. 338).

6) Instructio virorum ecclesiasticorum

This text by Joannes Amelius is the final instructional tract for priests to appear in the compilation, and it includes sections on the abuses of indulgences and excommunication. The author dedicated the work to ‘F. Dominico de Ferro dive Gertrudis observantia[m] in Buschoducis p[ro]fesso’ (fol. 1v). The dedicatee has been identified as Dominicus Corstiaen van den Yserz, a priest living at Sint-Geertruiklooster, a convent in Den Bosch (cf. Brabant Collectie blog post 2014).

This edition is notable for its attractive woodcut to the title-page depicting a monk in a scriptorium, surrounded by books. It was produced by Regnault Chaudière and Jean du Pré (II), the latter also connected with publication 3 above. Regnault Chaudière (d. 1544?) was a printer and bookseller who held the title of libraire-juré at the University of Paris.

Moreau infers that this edition was printed around the year 1520 based on the date that follows the dedication. This is one of four known editions of Joannes Amelius’s text, all of which were printed in Paris in 1520 or c.1520.

7) Les reformatio[n]s des previleges […]

The final publication in the compilation moves away from the genre of instructions for priests. It is also the only item in the Sammelband in French, and the only item to use Bâtarde type (the body text type is similar to—though not identical with—Bâtarde B7 in Isaac and Shaw 2020).

Specifically, the final publication is a rare edition of two royal acts issued during the reign of Louis XII. The first, given at Romorantin on 12th of May 1499, concerns the privileges of students at the University of Paris (for an edition of the text, see Pardessus 1849, pp. 221–224). Scholarly privileges were a ‘bestowal of peculiar rights, privileges, and immunities upon university graduates, who would thus be set apart from the ordinary run of the population’ (Kibre 1954, p. 543).

The second, given at Blois on the 12nd of November 1506, is a royal order controlling currency, including a list of different coins, running over three pages, with weight and value. A woodcut at the end of the publication depicts knights fighting on horseback, which has no obvious bearing on the textual contents. This pamphlet was printed by Guillaume Nyverd, a Parisian printer active c.1500– 1519 and one of the most prolific printers of royal acts at the time (FRA vol. 1, p. 123).

Nyverd in fact printed two very similar editions of the text at the same time, which can be distinguished by the composition of the colophon. There appear to have been at least two earlier editions of the royal act concerning university privileges (FRA 5611, [1499], FRA 5612, [1499]). In 1506, i.e. the same year in which our edition was printed, another Parisian printer produced an edition of royal ordinances that contains both of the acts found here (see BNF FRBNF33851076).

Compilation and Reading Practices

Several annotations in this volume suggest that former users/owners were priests, which is unsurprising given the prevalence of instructional material for priests in the volume. Firstly, one would assume that a priest would be the kind of reader most likely to spot the mistake in the mass phrases that has been corrected in the margin of publication 4—especially because the error occurs during a prayer that the priest is supposed to say ‘in mente’ (i.e. in the mind). Secondly, it appears that Jacques Prenost [or Prevost] may have been a canon (see provenance 2).

Equally interesting is an annotating hand that we shall refer to here as ‘Hand A’ (c.1700?). Hand A’s annotations seem to suggest close attention to practical matters relating to becoming a priest. For example, in publication 3, hand A underlines and adds nota bene marks to various sections including a passage explaining the age requirements to be ordained as a subdeacon (18), deacon (20), and priest (25).

Similarly, in publication 5, hand A uses underlining and keyword extraction to flag a section on the seven holy orders. Yet hand A also appears to have been interested in material in the Sammelband that falls outside the instructions for priests genre. For example, hand A adds a nota bene in publication 2, a satirical investigation of papal power. Hand A may also be responsible for underlining passages in the biographical section on Chilon of Sparta in publication 1.

Ultimately, it remains unclear whether publications 1, 2, and 7 were deliberately sandwiched around a more obviously cohesive group of material on instructions for priests, or whether the binder simply had a group of similarly sized pamphlets to hand. Regardless, it is intriguing to find that at least one reader seems to have had interests that spanned multiple genres in this Sammelband.

Top to bottom (left): publications 1, 2, and 3.

Top to bottom (right): publications 3, 5, and 5.

Bibliography

Publication 1: Not in BM STC Fr. 1470–1600, BP16, CCFr, FB, Girard & Le Bouteiller, Moreau, or USTC. We note OCLC 881707742, which has format, foliation, collation, and title wording all matching the present edition, and like ours has a Marnef device. There are no holding institutions connected with this OCLC record. This OCLC record refers to Adams B3321, but the Newnham College Cambridge copy of Adams B3321 has a device belonging to Jean Petit (as discussed above).

Publication 2: BP16 103534, Erasmus Online 1089, FB 69275, Moreau II 1871, USTC 183845 (not identical with BP16 103533, Erasmus Online 1090, FB 69276, Moreau II 1870, USTC 183844). USTC records this as a lost book, yet Erasmus Online, Moreau, and OCLC and show copies in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France and Rotterdam Public Library. We note that the copy of Dialogus… [Jean de Gourmont, c.1518] in Cambridge University Library is not identical with the present edition.

Publication 3: BP16 103757, FB 74636, Moreau II 2094, USTC 183933. BP16, FB, Moreau, OCLC, and USTC and show copies in the Bibliothèque Sainte Geneviève, the British Library, Oxford Corpus Christi College Library, and the Royal Danish Library.*

Publication 4: Not in BM STC Fr. 1470–1600, BP16, CCFr, FB, Girard & Le Bouteiller, Moreau, OCLC, or USTC.

Publication 5: Not in BM STC Fr. 1470–1600, BP16, CCFr, FB, Girard & Le Bouteiller, Moreau, OCLC, or USTC.

Publication 6: BP16 103890, FB 52953, Moreau II 2227, USTC 183992. USTC lists this as a lost book, yet BP16, Moreau, and OCLC show copies at the Bibliothèque Saint-Geneviève (3), Chantilly Musée Condé, Sevilla Biblioteca Capitular y Colombina, Tilburg University, and the University of Amsterdam.*

Publication 7: FB 35152, FRA 5634, USTC 58456 (not identical with FB 35151, FRA 5635, USTC 67994). FB, FRA, OCLC, and USTC show copies at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France and Universiteitsbibliotheek Leiden.

*We note that although publications 3 and 6 have records on the Bibliothèque Nationale de France Catalogue général, it appears that the only Parisian copies of both publications are in the Bibliothèque Sainte Geneviève.

Secondary Literature

Adams, H. M., Catalogue of books printed on the continent of Europe, 1501–1600, in Cambridge libraries (London: Cambridge University Press, 1967). [abbreviated as Adams]

Alexandre, Jean-Louis et al., Reliures médiévales de la médiathèque d’Orléans (Turnhout: Brepols, 2004).

Bibliographie des éditions parisiennes du 16e siècle, last accessed 3 March 2023 via https://bp16.bnf.fr/ [abbreviated as BP16]

Braband Collectie Blog, 26 March 2014, post entitled ‘Instructio virorum ecclesiasticorum’, last accessed 3 March 2023 at https://brabant-collectie.blogspot.com/2014/03/instructio-virorum-ecclesiasticorum.html

Duffy, Eamon, The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England 1400–1580, 2nd edn (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005)

Erasmus Online Database, last accessed 10 March 2023 via https://www.bibliotheek.rotterdam.nl/erasmus-online-database

Girard, Alain R. and Anne Le Bouteiller, Catalogue Collectif de livres imprimés a Paris de 1472 a 1600 conservés dans les bibliothèques publiques de Basse-Normandie, Bibliotheca Bibliographica Aureliana CXXVIII (Baden-Baden: V. Koerner, 1991). [abbreviated as Girard and Le Bouteiller]

Haebler, Konrad, Verlegermarken des Jean Petit (Halle (Saale): Ehrardt Karras G.B.B.H, 1914).

Isaac, Frank, revised and completed by David J. Shaw, A Typographical Catalogue of books printed in France 1501–1520 in the British Library (Developed as a MediaWiki app by David Shaw 2020). Last accessed 03/03/2023 via https://france1501to1520.djshaw.co.uk/index.php?title=Main_Page

Kibre, Pearl, ‘Scholarly Privileges: Their Roman Origins and Medieval Expression’, The American Historical Review 59, no. 3 (1954): 543–67.

Kim, Lauren Jee-Su, ‘French Royal Acts Printed Before 1601: A Bibliographical Study’ (Doctoral thesis, University of St Andrews, 2008). [abbreviated as FRA]

Copeland, Rita, ‘Behind the Lives of Philosophers: Reading Diogenes Laertius in the Western Middle Ages’, Interfaces: A Journal of Medieval European Literatures 3 (2016): 245–63.

Pardessus, J. M. (ed.), Ordonnances des Rois de France de la troisième race…, vol. 21 (Paris, de l’imprimerie Nationale, 1849).

Pettegree, Andrew, Malcolm Walsby and Alexander Wilkinson, French Vernacular Books: Books published in the French Language before 1601, 2 vols. (Leiden: Brill, 2007); Andrew Pettegree and Malcolm Walsby, Books published in France before 1601 in Latin and Languages other than French, 2 vols. (Leiden: Brill, 2011). [abbreviated as FB]

Renouard, Philippe, Les Marques typographiques parisiennes des XVe et XVIe siècles (Paris: Champion, 1926). [abbreviated as Renouard, Marques]

Moreau, Brigitte, Inventaire Chronologique des éditions parisiennes du XVIe siècle, d’après les manuscrits de Philippe Renouard, 4 vols. (Paris, 1972–1993). [abbreviated as Moreau]

Short-title catalogue of Books printed in France and of French books printed in other countries from 1470 to 1600 in the British Museum, repr. (London: British Museum, 1966), and the Supplement (London: British Library, 1986). [abbreviated as BM STC Fr. 1470–1600]

Stigall, John Oliver H., ‘The “De vita et moribus philosophorum” of Walter Burley: An edition with introduction’ (Doctoral thesis, University of Colorado, 1956).

Walsby, Malcolm, Booksellers and Printers in Provincial France 1470–1600 (Leiden: Brill, 2020).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Jürgen Dinter (Antiquariat Jürgen Dinter, Cologne), Mitch Fraas (Kislak Center, University of Pennsylvania), Eve Lacey (Newnham College, Cambridge), Nicolas Malais (Cabinet Chaptal, Paris), Professor Nicholas Pickwoad, Christin Schwabe (Universitäts- und Stadtbibliothek Köln), and Liam Sims (Cambridge University Library) for assisting us with our research

Sian Witherden, March 2023